View the full Sydney Harbour Bridge collection on the Archives & History Resources webpage.

In pictures: Celebrating 91 years of the Sydney Harbour Bridge

Explore the landmark that has shaped the physical and social landscape of our city.

Before the bridge

While the building and management of the Sydney Harbour Bridge is a NSW Government responsibility, the City of Sydney Archives includes lots of historical gems about the bridge’s history.

Regular ferry services between the city and the north began in 1850. By the early 1920s, 5 major ferry services transported 13 million passengers a year.

In 1922, the state government passed the Sydney Harbour Bridge Act to authorise the construction of a bridge across Sydney Harbour from Dawes Point to Milsons Point.

View in the City of Sydney Archives.

- Credit: Milsons Point ferry base looking south towards Harbour Bridge works at Dawes Point, 1932 (City of Sydney Archives, A-00083034)

Remodelling city streets

The effects of the new bridge would spread well into the streets of the city. As work began on the construction of the bridge in 1923, Lord Mayor David Gilpin approved a conference to consider the remodelling of the city.

This plan from 1925 shows suggestions to widen and extend city streets to deal with the heavy traffic congestion expected from the bridge.

Council considered proposals to construct a crescent to connect the bridge with York, Clarence and Kent streets, as well as an extension of Martin Place across George Street to York Street and the widening of York Street from Martin Place to Druitt Street. The valuer general estimated the total cost of extending Martin Place and widening York Street to be around £1.2 million, about $2.5 million in today’s money.

View in the City of Sydney Archives.

- Credit: Crescent connecting Sydney Harbour Bridge approach with York, Clarence and Kent Streets, Sydney, 1925-1927 (City of Sydney Archives, A-00113491, p75)

On approach

The southern approach to the Sydney Harbour Bridge extending over pairs of granite-faced concrete pillars towards an emerging pylon at the end of Dawes Point/Tar-Ra.

The approach spans at either side of the harbour were supported by timber falsework. A 25-tonne electric crane created the steelwork of the approach on top of the timber falsework. The lower portion of the pylons, which reached deck level, supported the approaching spans and provided a foundation for the main bearings of the bridge, upon which the arches would come to rest.

View in the City of Sydney Archives.

- Credit: Sydney Harbour Bridge, circa 1926 (City of Sydney Archives, A-00057834)

The arches

The first sections of steel for the arches were placed in position on the southern side in October 1928, outpacing work in the north. In January 1930, work stopped for 72 days to allow the north to catch up.

This photograph, looking south towards Dawes Point /Tar-Ra, shows the 2 arches of the bridge soon to be joined above the harbour.

At nearly midnight on 19 August 1930, almost 2 years after the arc was begun, the 2 arches came together on a central bearing pin.

The cost of constructing the bridge was nearly £10 million, about $853 million in today’s money.

View in the City of Sydney Archives.

- Credit: Two arches of the Sydney Harbour Bridge, 1930 (City of Sydney Archives, A-00012676)

Opening preparations

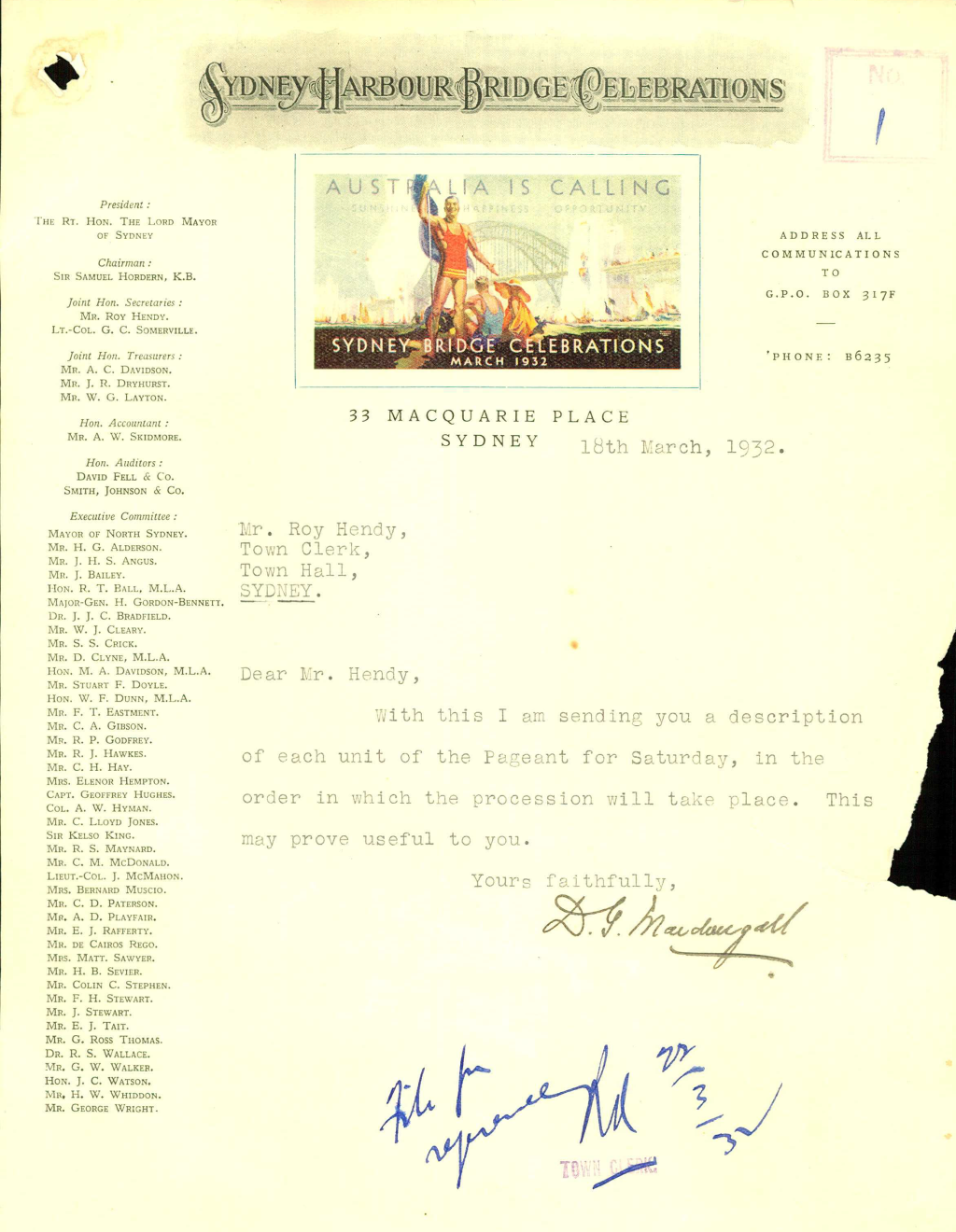

Many people saw the bridge opening as a chance to put the world’s eyes on Sydney and NSW, and requested a meeting with Sydney’s Lord Mayor.

This letter prepared by the Lord Mayor Joseph Jackson invited 200 representatives from government bodies and professional associations to a meeting in Sydney Town Hall. The guests formed committees and spent 6 months organising a week of pageantry and displays to mark the bridge opening.

View detailed descriptions of all planned events and a hand-drawn assembly plan, plus letters from businesses that wanted to participate in the celebrations, offering services such as printing, flower arrangements and shop window display. There was even an offer from 2 ‘north shore misses’ to play the parts of Sir Henry and Lady Parkes in the historical pageant.

- Credit: Public meeting to arrange celebrations for the opening of the Sydney Harbour Bridge, 1931-1932 (City of Sydney Archives, A-00120141, p261)

Good sports

Many amateur sports associations wanted to use the week-long carnival to publicise their activities and gain international interest. The NSW Bowling Association substituted its annual Country Week with a bowling carnival to coincide with Bridge Week.

This poster was sent to clubs throughout the Commonwealth, New Zealand and British Isles to advertise the bridge opening and promote the competition.

View in the City of Sydney Archives.

- Credit: Applications for hire of Sydney Town Hall during Sydney Harbour Bridge Week, 1931-1932 (City of Sydney Archives, A-00120286, p50)

Lord Mayor's Ball

Lord Mayor Samuel Walder hosted a celebration ball at Sydney Town Hall on the eve of the bridge opening. This photo shows the entry card sent to invitees, including members of the House of Representatives, Senate and local councils.

The town clerk's department correspondence file contains acceptances and apologies, details about decorations, music and dance programs, an 8-page final guest list and a full running order of the event.

View in the City of Sydney Archives.

- Credit: File - Lord Mayor's ball to commemorate opening of Sydney Harbour Bridge, 1932 (City of Sydney Archives, A-00120307 pp 5,6,15)

Opening day pageant

The centrepiece of the opening celebrations was the pageant. In a letter to the City of Sydney, the celebrations committee described it as “the most spectacular pageant ever seen in the southern hemisphere… Only those who have been privileged to see the floats in the course of construction can have any idea of their magnificence and beauty. In all there will be 27 floats – 8 in the historical section, 6 in the primary produce section and 13 in the floral section including one representing the British Empire. No less than 18 bands will march.”

The Sydney Harbour Bridge celebrations committee file includes lots of detail about the pageant.

Sydney Town Hall played its part during the pageant, hosting 100 people to watch from the entrance and allowing use of the basement as a casualty station for the St John’s Ambulance Brigade.

- Credit: File - Details of pageant for Sydney Harbour Bridge opening, 1932 (City of Sydney Archives, A-00120398, p5)

Celebrated in song

10 days after the opening celebrations, town clerk Roy Hendy received a letter from John Bepper, including a copy of a celebratory song he had composed called Our Harbour Bridge also known as The Bridge Two-Step. He hoped that organist Ernest Truman would play it on the organ at one of the council’s recitals. Mr Bepper wrote that the Boston Two Step could be danced to his number. Mr Turman agreed to play it on the grand organ at a suitable occasion.

View in the City of Sydney Archives.

- Credit: File - To bring song 'Our Harbour Bridge' to the attention of City Organist, 1932 (City of Sydney Archives, A-00120402, pp8, 9)

Bridge dangers

As Sydneysiders began to live with the bridge, they experienced new challenges. In November 1935 a City of Sydney engineer wrote to the town clerk advising that an employee from his department had been working below the bridge when a 10-pound piece of metal fell near him.

There were multiple instances of metal objects such as brake blocks, bolts, iron nuts and pieces of brass falling from the bridge onto workers or members of the public in Dawes Point Park.

The engineer also noted many spots of oil on George and York streets falling from the trains overhead and was worried that the public would complain if it stained their clothes.

In January 1938 the park was closed for a while as additional planking was installed. By August 1939, the Railway and Road Transport Department indicated that it was replacing the rail anchors used on the bridge, as the original design had not been entirely suitable. The department erected additional planking and wire mesh screen between the decking and the parapets. There was no further trouble.

View in the City of Sydney Archives.

- Credit: File - Danger from materials falling in Dawes Point Park from Sydney Harbour Bridge, Dawes Point, 1935-1939 (City of Sydney Archives, A-00122147, p34)

Traffic

This enigmatic image comes from the Percy Bryant Collection, donated to the City archives in 2021 by the family of Percy Bryant. Percy was an amateur photographer who loved capturing Sydney and the harbour on film. Mr Bryant was employed by the railway prior to the Depression and joined the Electric Light Shop. His opportunities to photograph Sydney’s centrepiece improved dramatically when the light shop moved its attention to wiring the new Sydney Harbour Bridge.

View in the City of Sydney Archives.

- Credit: Sydney Harbour Bridge heading north, Bradfield Highway Sydney, 1937 (City of Sydney Archives, A-01141929)

On foot, 1932

Following the opening pageant, the bridge was opened to pedestrians who had exclusive use of the roadway until midnight. Thousands of people made the crossing. 50 years later in 1982, to mark the anniversary the bridge was closed to traffic again and thousands more crossed.

View in the City of Sydney Archives.

- Credit: Sydney Harbour Bridge, 1932. (City of Sydney Archives, Photographer: Percy Bryant, A-00034464)

On foot, 2000

People have continued to cross the bridge on foot for sport, spectatorship, protest and celebration. On 28 May 2000, 250,000 people crossed the bridge to support meaningful reconciliation between Australia’s Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities. The event was part of the Council for Aboriginal Reconciliation’s Corroboree 2000. The Bridge Walk for Reconciliation was the largest demonstration of public support for a single cause that has ever taken place in Australia.

Later that same year, Olympic runners crossed the spectator-lined bridge during the men’s and women’s marathons. In 2007, pedestrians streamed across a vehicle-free deck to celebrate the bridge’s 75th anniversary.

- Credit: Walk for Reconciliation, Sydney Harbour Bridge, 2000 (City of Sydney Archives, Photographer: C.Moore Hardy, A-00069112)

Celebrations

In 1976, the Sydney Committee decided to transform the failing Waratah Festival into the Festival of Sydney, using New Year’s Eve as the launch. Celebrations included decorated boats, music, and a “spectacular fireworks display at midnight”.

The Sydney Harbour Bridge has been the focal point of Sydney New Year’s Eve firework displays since the late 1990s, inspired by fireworks on New York’s Brooklyn Bridge in 1983 to celebrate its centenary.

This photo shows the 2006 midnight fireworks. A question mark was shown in the nights leading up to the celebrations. It was revealed as the curved end of a coat hanger – an homage to the bridge’s famous nickname.

Traffic stopped for Sydney WorldPride celebrations when 50,000 attendees wearing their brightest colours marched across the landmark in March 2023.

View in the City of Sydney Archives.

- Credit: New Year’s Eve fireworks above the Sydney Harbour Bridge, 2006 (City of Sydney Archives, A-00064983)