Sydney Culture Walks is the ideal companion for discovering the city on foot. Remembrance is an easy 50-minute walk taking in some of the more prominent memorials to WWI.

Sydney’s streets and civic spaces bear witness to World War I

You’ll be surprised how many traces can be found in the fabric of our city.

Cenotaph, Martin Place

The naturalistic bronze sentinels flanking the 20-tonne granite Sydney Cenotaph at Martin Place were modeled on two World War I servicemen, private William P Derby (1870–1936) and leading signalman John William Varcoe (1897–1948).

The ‘empty tomb’ gave Sydneysiders a place to remember loved ones, who lay in cemeteries on the other side of the world or were missing with no grave.

The Anzac Day dawn service, a ritual now observed throughout Australia and New Zealand, started here. In the early hours of Anzac Day in 1927, a small group of returned soldiers wending their way home from an Anzac Day Eve function, saw an elderly woman place flowers at the cenotaph. They bowed their heads alongside her and resolved to gather each year for a dawn service.

- Credit: BdB/City of Sydney

‘Sacrifice’ by Rayner Hoff, Anzac Memorial, Hyde Park

Step inside the Anzac Memorial when you next walk through Hyde Park and you’ll find this striking bronze sculpture by Rayner Hoff. A mother, sister and wife nursing an infant bear a Spartan warrior dead on his shield.

The city’s main war memorial was funded by public subscription and completed in 1934.

The exterior features 20 monumental stone figures sculpted by Hoff in his studio at East Sydney Technical College. Look for the airman and matron on the southwest and northwest corners. Hoff served with the British Army on the western front, and these figures offer, in contrast to the allegorical Sacrifice, a true-to-life portrayal of Australian World War I servicemen and women. Hoff’s proposals for the east and west pedestals proved too controversial and were never realised.

The state government recently restored and extended the memorial. The City of Sydney contributed to the work, officially opened by Prince Harry in October 2018.

- Credit: BdB/City of Sydney

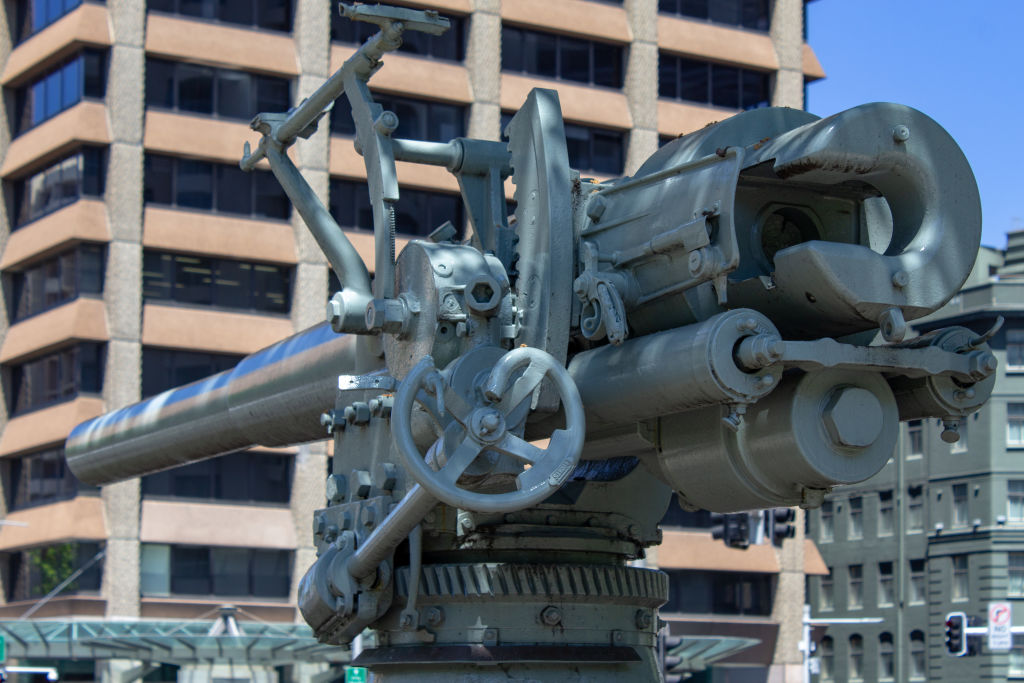

‘Emden’ gun, Hyde Park

Thousands of captured weapons were given to towns across the country after the armistice in 1918. But the first trophy of Australia’s war was a gun taken from the German raider SMS Emden, destroyed by HMAS Sydney off the Cocos Islands on 9 November 1914.

The 4 inch Krupp gun was presented to the citizens of Sydney by the federal government. The council mounted the gun in the southeast corner of Hyde Park in December 1917.

- Credit: BdB/City of Sydney

Diana bringing harmony to the world, Hyde Park

At the northern end of Hyde Park is a much photographed fountain that celebrates life after war. The mythic figure of Apollo stands atop the fountain, giving life to all nature. Surrounding him are 3 groups of figures. Pictured is Diana, goddess of the hunt, representing purity, charity and harmony.

The Archibald Fountain was commissioned by the Francophile journalist and publisher J F Archibald to commemorate the bond forged between Australia and France in war.

John Feltham (later Jules François) Archibald, was the founder and namesake of the Archibald Prize for portraiture.

- Credit: BdB/City of Sydney

‘Dead Soldier’ by George Lambert, St Mary’s Cathedral

George Lambert’s recumbent bronze soldier was commissioned by the Catholic Sailors and Soldiers Memorial Committee. It recalls a medieval sarcophagus found in a European church. “I have produced a serious combination of a dead tin-hatter of the French front and a saint,” he wrote.

Lambert was an official Australian war artist during World War I. He went to Gallipoli in 1919 with Charles Bean, where he made the sketches for Anzac, the landing 1915, the largest painting in the Australian War Memorial.

- Credit: BdB/City of Sydney

Bullet damage? Central station

The Battle of Central Station took place on 14 February 1916 at the end of a highly charged day when trainee soldiers rioted in the streets of Sydney.

That morning, new recruits from the camp at Casula, fueled first by injustice at having to do extra drill, then by alcohol looted from the hotels at Liverpool, commandeered trains into the city. A rowdy column of mutineers marched through the city, raiding fruit carts, looting shops and smashing the windows of the German Club.

In the evening, an angry mob fought with police and military pickets at Central station. When shooting broke out, a 20-year-old recruit in the Light Horse was killed and 7 were wounded, among them a civilian. The damage to a marble column near platform 1 is said to be from one of the bullets fired.

The riot – as described by newspapers – or strike – as insisted upon by the rioters – led to the early closing of pubs in NSW and the 6 o’clock swill.

- Credit: BdB/City of Sydney

Anzac Parade and Anzac Obelisk, Moore Park

Many memorials were utilitarian in nature. On 9 January 1917, the Lord Mayor of Sydney proposed that the newly widened Randwick Road be named Anzac Parade. It was the first of many thoroughfares to bear the sacred name.

A stone obelisk was unveiled at the opening of the road in March 1917. It was the focal point for the city’s Anzac Day commemorations for many years as it predated the Sydney Cenotaph in Martin Place and the Anzac Memorial in Hyde Park.

Today the obelisk stands in Moore Park East.

- Credit: BdB/City of Sydney

Moore Park Cricket Association Memorial Drinking Fountain

Drinking fountains also offered a utilitarian memorial to those who served. This example, at the intersection of Cleveland and South Dowling streets, names 33 members of the Moore Park Cricket Association who fell in World War I. Fittingly, cricket continues to be played on the ovals just a boundary throw away.

Other interesting examples of memorial fountains can be seen in Sydney. A granite and sandstone obelisk in Hyde Park north, on the corner of Elizabeth and Park streets, was erected by the Grand United Order of Oddfellows. A sandstone monument and water bubbler at Woolloomooloo was placed opposite the gates through which the soldiers passed on their way to war. It was commissioned by the Centre for Soldiers’ Wives and Mothers on behalf of ‘the women of New South Wales’.

- Credit: BdB/City of Sydney

Restoring the Rozelle tramsheds ‘digger’

This statue, dating from 1916, was commissioned and paid for by Rozelle tram workers. It was the first such ‘digger’ sculpture to be raised as a memorial in Australia.

Unusually for its time, the statue depicts an Australian soldier in a relaxed pose, his slouch hat turned down all round, an open collar and rolled up sleeves, holding a rifle with the bayonet fixed and ready for battle.

The statue has recently been restored and rededicated.

Other distinctive local memorials can be found at Glebe, Pyrmont and Redfern.

- Credit: Katherine Griffiths